Guaranteeing k Samples in Streaming Sampling Without Replacement

tl;dr

When doing streaming sampling without replacement of a finite data set of known size $N$ in Pig, you can do

data = LOAD 'data' AS (f1:int,f2:int,f3:int);

X = SAMPLE data p;

for some number $p$ between 0 and 1. If you need $k$ samples, typically you’d naively choose $p = k/N$, but this only gives you $k$ on average – sometimes less, sometimes more. If you must have at least $k$ samples use

\begin{equation} p = \frac{1}{N}\left(k + \frac{1}{2} z^2 + \frac{1}{2}\sqrt{z^2(4k + z^2)}\right). \end{equation}

The table below helps in choosing $z$. It reads like this: setting $z$ to the specified value guarantees you’ll get at least $k$ about $CL$ of the time for any $k$ larger than 20 or so; for smaller $k$ you’ll do even better.

| $z$ | $CL$ |

|---|---|

| $0$ | $\geq 50\%$ |

| $1$ | $\geq 84\%$ |

| $2$ | $\geq 98\%$ |

| $3$ | $\geq 99.9\%$ |

| $4$ | $\geq 99.997\%$ |

| $5$ | $\geq 99.99997\%$ |

You’ll get more than $k$ back, so as a final step maybe you’ll randomly shuffle the resulting sample and select the top $k$, assuming $k$ is not enormous.

If you’re unlucky enough to get less than $k$ back, try again with a new random seed.

Problem statement

You have a data set of finite size $N$ and you want $k$ random samples without replacement. A computationally efficient procedure is to stream through the data and emit entries with some probability $p$ by generating a uniform random number at each entry and emitting the entry if that number is $\leq p$. Here’s what I just said in pseudocode:

given table of size N

given desired number of sample k

let p <= k/N

for each row in table

if rand_unif() ≤ p

emit row

end if

end for

Pig provides this functionality with

data = LOAD 'data' AS (f1:int,f2:int,f3:int);

X = SAMPLE data 0.001;

Hive provides this API

SELECT * FROM data TABLESAMPLE(0.1 PERCENT) s;

but it behaves differently as it gives you a 0.1% size block or more of the table. To replicate the pseudocode behavior maybe you’d do

SELECT * FROM data WHERE RAND() < 0.001;

These queries are probabilistic insofar as the size of the output is size $k = 0.001 N$ only on average. Algorithms in the reservoir sampling family will give you exactly $k$ from a stream, but these are complicated solutions if you’re just issuing Hive/Pig queries during an ad hoc analysis. Googling produces language documentation and posts such as “Random Sampling in Hive”, which underscore the problem.

I got to thinking about what happens when you place stronger requirements on the final sample size in this kind of setting. I’ll touch on three requirements.

Requirement 1. Produce approximately $k$ samples.

Requirement 2. Produce at least $k$ samples.

Requirement 3. Produce exactly $k$ samples.

My assumptions going into this are

- The data set is static, large, distributed and finite.

- Its size is known up front.

- It may be ordered or not.

- There is no key (say, a user hash, or rank) available for me to use, well distributed or otherwise.

Requirement 1: approximately $k$

In this case just use $p = k/N$. On average you get $k$, with variability of about $\pm\sqrt{k}$.

Requirement 2: at least $k$

At least $k$ can be guaranteed in one or sometimes (rarely) more passes. I’ll develop a model for the probability of generating at least $k$ in one pass. To strictly guarantee at least $k$ you would have to check the final sample size and, if it undershoots, make another pass through the data, but you can tune the probability such that the chance of this happening is very low.

Random sampling of a big data stream as a Poisson process

The probabilistic emission of rows in the pseudocode above can be modeled as a Poisson process. The number of events, or points emitted, over the entire big data set follows a Poisson distribution. The Poisson distribution, $\mathrm{Poisson}(\lambda)$, is fully described by a single parameter $\lambda$, which is the mean rate of events over some fixed amount of time, or in our case, the mean number of samples over one pass. That is, $\lambda = Np$ in one pass over the full data set.

The expectation of the the number of samples $X$ is $\mathrm{E}(X) = \lambda$, and the variance is $\mathrm{Var}(X) = \lambda$.

Random sampling of small data as a Bernoulli process

Despite all the hype it’s still sometimes fun to think about not-big data. In this case you can think about random sampling without replacement as a Bernoulli process, so the number of emitted points is distributed as $\mathrm{Binomial}(N, p)$. You’re doing $N$ coin tosses with a coin biased as $p$.

In the limit of large $N$ and fixed $p$, $\mathrm{Binomial}(N, p) \to \mathrm{Normal}(\mu = Np, \sigma^2 = Np(1-p))$. If $p$ is also small, $\mathrm{Binomial}(N, p) \to \mathrm{Normal}(\mu = Np, \sigma^2 = Np)$.

In the limit of large $N$ and small $p$, $\mathrm{Binomial}(N, p) \to \mathrm{Poisson}(\lambda = Np)$, which is what I’ve already described in the previous section.

You might guess by the transitive rule that $\mathrm{Poisson}(\lambda = Np) \to \mathrm{Normal}(\mu = \lambda, \sigma^2 = \lambda)$ when $Np$ is large and $p$ is small. This is what I’ll talk about next.

Large $\lambda$

When $\lambda$ is large the Poisson distribution converges to a normal distribution with mean $\lambda$ and variance $\lambda$. $\lambda$ can be as small as 20 for $\mathrm{Normal}(\lambda,\lambda)$ to be a good approximation. This is convenient because all of the usual Gaussian statistics can be applied.

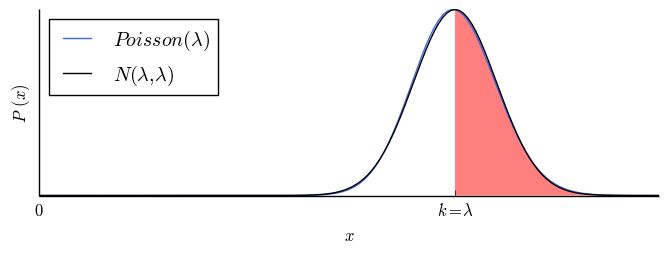

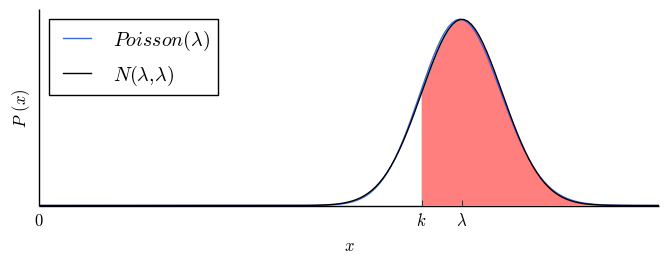

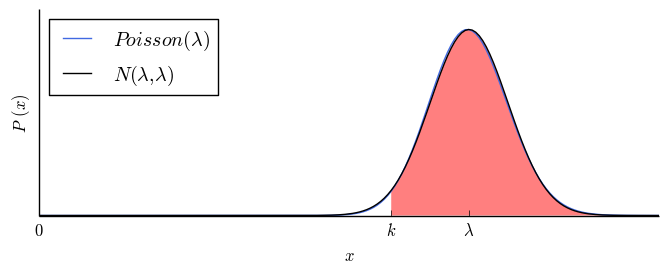

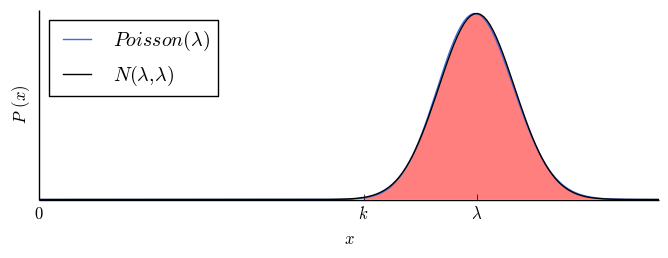

The number of times you get at least $k$ samples is described by a one-sided $z$-statistic and can be read off of a standard $z$-score table. $z$ is the number of standard deviations from the mean. The probability of getting at least $k$ samples is $CL = 84\%$ at $z = 1$. Here are four such sets of useful values, with illustrations.

$z$ table: area under $\mathrm{Normal}(\lambda,\lambda)$ above $k = \lambda - z\sqrt{\lambda}$.

| $z$ | $CL$ | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $50.0\%$ |  |

| $1$ | $84.1\%$ |  |

| $2$ | $97.7\%$ |  |

| $3$ | $99.9\%$ |  |

To guarantee at least $k$ samples in $CL$ of your queries you’d choose $p = \lambda(k,z)/N$, where $\lambda(k,z)$ solves $\lambda - z\sqrt{\lambda} = k$. In other words, you’d choose a rate $p = \lambda/N$ such that $k$ is $z$ standard deviations below $\lambda$. The (useful) solution is $\lambda(k,z) = k + \frac{1}{2} z^2 + \frac{1}{2}\sqrt{z^2(4k + z^2)}$.

Monte Carlo gut check

To prove to myself the math is right, I’ll run 8 parallel Monte Carlo simulations of 10,000 iteration each in bash. I’ll try to sample $k=100$ out of $N=1000$ for different values of $z$.

function monte_carlo () {

awk "$@" -v seed=$RANDOM '

BEGIN {

lam = k + 0.5*z**2 + 0.5*sqrt(z**2*(4.0*k + z**2))

p = lam/n_data

srand(seed)

for (j=1;j<=n_experiments;j++) {

emit=0

for (i=1;i<=n_data;i++) {

if (rand()<=p) {

emit++

}

}

if (emit>=k) {

n++

}

}

print seed,k,lam,p,n_data,n

}' ;

}

export -f monte_carlo

parallel -N0 monte_carlo -v n_experiments=1e4 -v n_data=1e3 -v k=100 -v z=0 ::: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

In one of the runs at $CL = 84\%$ I got at least $k = 100$ samples 8,664 out of 10,000 times. In this case, $\lambda = 110.5$. Here’s a table of typical results at different $z$ value settings.

Monte Carlo runs of 10,000 iterations each, setting $k = 100$.

| $z$ | $CL$ | num $\geq k$ | $\lambda$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0$ | $\geq 50\%$ | $5\,183$ | $100.0$ |

| $1$ | $\geq 84\%$ | $8\,664$ | $110.5$ |

| $2$ | $\geq 98\%$ | $9\,846$ | $122.1$ |

| $3$ | $\geq 99.9\%$ | $9\,998$ | $134.8$ |

| $4$ | $\geq 99.997\%$ | $10\,000$ | $148.8$ |

It’s clear from the simulations that the true confidence is slightly higher than advertised, but this is expected. There are two sources of bias: finite $k$ in the central limit theorem approximation, and discreteness of the random variable at $k$. Given how I implemented the Monte Carlo, both push the true confidence higher, so the stated lower limit on confidence holds.

The “guarantee” of at least $k$ in a single pass is a probabilistic one, and it implies that at, say, a $CL = 99.9\%$ specification I would have to go over the data set a second time roughly 1 out of every $(1-CL)^{-1} = 1\,000$ times that I undertook this whole exercise. At this specification the need to rerun is rare, but it will eventually happen. When it does, I’d have to go through the full data set again with a smaller $p$ to get a fair random sample, specifically, I would reapply the same rule for a new $\lambda(k\to k-k_1,z)$, where $k_1$ is the actual sample size that the first iteration yielded me. It is even rarer that I’d have to do a third pass at $CL = 99.9\%$. This case happens one in a million times.

It’s fairly obvious to me just thinking about it that it’s better to set $CL$ high and try to do just one pass than it is to set $CL$ low and to do multiple passes. For example, if $CL = 50\%$ ($z = 0$) then nearly half the time I’d be rerunning twice or more times to build up a fair sample. Passes over big data are expensive as it is, so it’s better to eat $k_1 - k$ too many samples in one pass than to have to do additional passes on the data.

Requirement 3: exactly $k$

Run the above, randomly shuffle and pick out the top $k$.

If you get less than $k$ you were just very unlucky. Run the whole thing again with a different random seed.

You may also consider implementing a reservoir sampler, but this is more work than is needed.

Comments